The most important risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is also maybe the most obvious: the process of aging itself. Indeed, the link between aging and Alzheimer’s might be the key to decoding the disorder—yet that link remains largely a mystery to science.

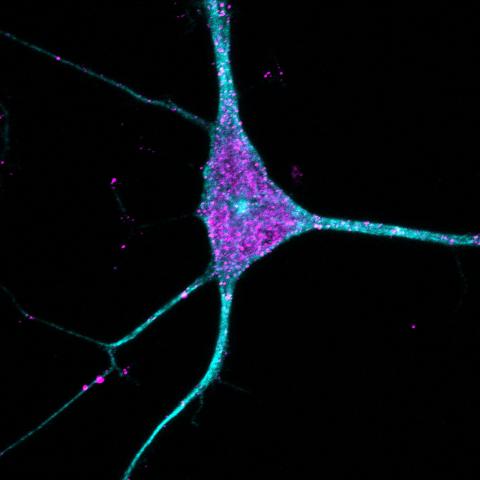

A significant part of the problem, said Judith Frydman, a professor of biology and genetics and a Wu Tsai Neuro affiliate, is that scientists don’t have great tools to study aging in cells such as neurons. As part of a Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience-funded project, Frydman and colleagues believe they have found a solution to this problem—so-called transdifferentiated neurons, or tNeurons, which are grown from human skin cells in the lab and maintain key molecular signatures of the aging process.

In a paper published March 25 in Nature Cell Biology, Frydman, research scientist Ching-Chieh Chou, and colleagues used these tNeurons to reveal new evidence that older cells often struggle to repair lysosomes—cells’ recycling centers—and that the breakdown of this system may be a key precursor to neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s.

Such findings were hard to come by with other techniques. The researchers might have studied brain tissues gathered post-mortem, but aging-related changes are not always apparent in those samples. Another possibility is to grow neurons—for instance carrying Alzheimer’s mutations—from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the basis for brain organoids, but that approach involves essentially rebooting cellular development, restoring cells to a youthful state, when what researchers really want is to study aging cells.

To address those challenges, the researchers turned to work by Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute affiliate Marius Wernig, a professor of pathology who has been developing tools to directly reprogram skin cells into neurons. Wernig and his lab make these tNeurons by introducing a set of molecules called transcription factors into cells. Transcription factors turn specific genes on or off in a given cell, which can completely transform how the cell functions—or even what type of cell it is. And, because tNeurons are produced directly from aged cells rather than stem cells, they retain the molecular and proteomic, or protein-related, signs of aging from the originals.

In their new paper, Frydman and her team grew tNeurons from the skin cells of eight healthy young, 12 healthy older donors, and 16 older donors with Alzheimer’s—on average 25.6, 70.3, and 70.4 years of age, respectively. Then, they looked at what exactly was going on inside tNeurons from the three groups, focusing on the various proteins present inside those cells.

Almost immediately, the team noticed that older tNeurons from people with Alzheimer’s spontaneously showed classic signs of the disease, including the accumulation of tangled tau proteins and amyloid beta—even though no such signs had been present in the donors’ skin cells.

“To me, it was surprising because it suggests all cells in the body of a person with Alzheimer’s have this vulnerability that manifests in neurons as the typical Alzheimer’s pathology,” Frydman said. That observation hints that neuroscientists could study Alzheimer’s or even test drugs using neurons grown from human skin cells rather than mice. “I think this is a powerful insight that could lead to powerful—and even personalized—diagnostics and therapeutic applications,” Frydman said.

Consistent with past research, the team’s analysis also revealed that Alzheimer’s was associated with damaged lysosomes.

But the team took that analysis farther and discovered that one cause of the damage lies in the system of proteins that helps repair or remove damaged lysosomes. That system starts to break down in older tNeurons, setting off a “vicious cycle,” Frydman said: If cells can’t repair damaged lysosomes, then they can’t rid themselves of toxic and misfolded proteins and other cellular refuse, which in turn further damages lysosomes. Left unchecked, that cycle will eventually kill the whole cell.

Chou said that the result is significant because it helps open up a “black box between lysosomal damage and cell death,” which had previously been attributed primarily to the build up of tau proteins and amyloid beta. “We were able to show that’s only a part of it. Failure to repair lysosomes is a key to neurodegeneration.”

Publication Details

Research Team

Study authors were Ching-Chieh Chou and Ting-Ting Lee from Stanford University's Department of Biology and Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Collaborative Research Network; Ryan Vest from Stanford's Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford Medicine's Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, The Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, and Qinotto, Inc.; Miguel A. Prado from Harvard University and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias; Joshua Wilson-Grady, Joao A. Paulo, Steven P. Gygi, and Daniel Finley from Harvard University; Yohei Shibuya and Marius Wernig from Stanford Medicine's Department of Pathology and the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine; Patricia Moran-Losada and Tony Wyss-Coray from Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, The Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute; Jian Luo from the Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research; Jeffery W. Kelly from the Scripps Research Institute; and Judith Frydman from Stanford's Department of Biology, Stanford Medicine's Department of Genetics, Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Collaborative Research Network, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

Research Support

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P01AG054407, P50AG047366, and P30AG066515), the Hevolution Foundation, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) initiative(ASAP-000282), the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research Postdoctoral Fellowship in Aging Research, the Paul F. Glenn Center for Biology of Aging Research at Stanford, the Life Sciences Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship and the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program in BrightFocus Foundation Grant, the Goldberg Fund Fellowship, and the Miguel Servet Programme (CP21/00017).

Competing Interests

Ryan Vest, Jian Luo, and Tony Wyss-Cory are co-founders of Qinotto Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.