Walking into the Spring Symposium and Research Showcase hosted by the Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience on May 7, one could feel a field at an inflection point.

The research presented—spanning molecular mechanisms to population-level interventions—signaled an ongoing shift in perspective toward understanding and enhancing the brain's intrinsic capacity for resilience, rather than focusing specifically on neurodegenerative diseases.

Kicking off the symposium, Knight Initiative Director Tony Wyss-Coray, the D.H. Chen Distinguished Professor of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, emphasized the wide range of research the initiative has been supporting. "We don't have enough time to show you all of it," he said, "but I'm extremely excited about what is happening and the momentum we're gaining.”

Redefining neurodegenerative disease

Kathleen Poston, the Edward F. and Irene Thiele Pimley Professor of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, opened the symposium with a case for reconceptualizing neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease in terms of biology as opposed to symptoms alone.

Poston’s recent work, for example, shows that new biomarker-based diagnostics may be significantly more accurate than clinical observation alone, which often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment.

The problem, Poston explained, is the mismatch between a patient’s observable behavior and what’s going on in their brain. "The clinical syndrome does not always encapsulate the biology, and the biology does not always describe everybody who has the clinical syndrome," she said.

However, new biomarkers are rapidly revolutionizing the field, Poston said. Technologies like the recently developed alpha-synuclein seed amplification assay, which detects molecular signs of disease in cerebrospinal fluid years before symptoms emerge, show promise for detecting the earliest signs of Parkinson’s.

Findings like that suggest the need for a reconceptualization of neurodegenerative disease, Poston argued. "These individuals aren't merely at risk for having a disease—they already have a disease. They're at risk for developing symptoms."

To prevent disease and enhance resilience doctors and researchers need to identify more biomarkers for early-stage neurodegenerative conditions, Poston said. And doing that, she said, requires progress toward a better understanding of the biology underlying these disorders.

Lived experience

Poston described this paradigm shift as prelude to a conversation with Bart Narter, a patient advocate who has lived with Parkinson’s disease for 13 years. Despite carrying the typically aggressive GBA gene mutation, Narter has demonstrated extraordinary resilience, maintaining significant mobility and independence.

In describing his experience, Narter emphasized the highly personal and variable nature of the disease. “If you’ve met one Parkinson’s patient, you’ve met one Parkinson’s patient,” he said.

Narter has participated in 72 studies since his diagnosis, motivated by the recognition that his role as a research participant is vital to accelerating progress toward a cure. He noted that as a patient, he is uniquely qualified to contribute to science in this way, and he urged researchers to consider practical barriers to patient participation, including transportation, the frustrations of app-based parking for a patient, and the fragmented scheduling of clinical visits alongside the many visits for research.

Asked what frightened him most about his condition, Narter emphasized what makes brain resilience so precious: "If they chopped off my arms, I'd still be Bart. And if they chopped off my legs, I'd still be Bart. But if they shut down my brain, I would not be Bart anymore."

New windows into brain function

A central challenge in studying brain resilience has been measuring neural health before symptoms of a disease appear.

To that end, Patrick Purdon, a professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine and a professor of bioengineering by courtesy, is studying how brain waves might be used to predict future cognitive decline. In studies of patients under anesthesia, Purdon and colleagues found that electrical patterns in the brain called alpha waves might indicate whether a patient would experience post-operative delirium, a condition that often affects older surgical patients and can lead to worsening cognitive decline.

Working with Knight Initiative investigators Martin Angst and Igor Feinstein in the Department of Anesthesiology, Purdon is working to discover potential connections between brain waves and molecular markers in the blood that spike during cardiac surgery—and which also predict future cognitive decline.

Purdon said that because patients' brain waves under anesthesia are simpler than when they’re awake, anesthesia may make it easier to see trends in brain health that would be otherwise hard to pick out. "We're observing brain health through the lens of anesthesia, which collapses brain activity down to just one frequency—one note," Purdon explained. "This simplification may reveal a larger, system-wide level of resilience that typically remains hidden." Purdon is next working on ways to measure these otherwise hidden signatures of brain resilience or cognitive decline without anesthesia.

Parsing cognitive decline

Elizabeth Mormino, an associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences, is taking a rather different approach. With Knight Initiative support, Mormino and her team are analyzing a bank of cerebrospinal fluid samples, which may help them understand why some individuals maintain cognitive function despite testing positive for early biomarkers of disease.

"Why do some people live to be very old but maintain optimal cognitive performance?" Mormino asked, stating a central question in resilience research. Her team's approach—combining PET imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, and fMRI brain scans during challenging memory tasks—has revealed how the brain's ability to distinctly process different visual categories decreases with both age and early Alzheimer’s pathology.

Particularly striking was their finding that different pathologies affect cognition in separable ways. For example, accumulating tau proteins—which have been connected to Alzheimer’s disease—appear to primarily impact memory, while alpha-synuclein—abnormal forms of which are linked to Parkinson’s—affects attention and visuospatial processing. "These distinct signatures may help us identify which individuals need monitoring for specific cognitive domains and potentially guide personalized interventions before functional independence is compromised," Mormino said.

Unexpected pathways to protection

Knight Initiative-funded research is also revealing unexpected therapeutic pathways—some at the cellular level and others at the population scale.

Jian Xiong, a Brain Resilience Postdoctoral Scholar in the lab of Chemical Engineering and Genetics Professor Monther Abu-Remaileh, presented research recently published in Nature on enhancing the function of brain cells’ lysosomes, the recycling and waste disposal system of all our cells. Xiong compared the brain to an aging machine: "During normal aging, our gears accumulate some rust, but when lysosome defects are present, the process accelerates dramatically, leading to more severely worn and damaged machinery."

His Knight Initiative-funded research identified the enzyme PLA2G15 as a key regulator of BMP, a crucial lipid for optimal lysosomal function. Remarkably, Xiong’s team found that inhibiting PLA2G15 enhanced lysosomal function and dramatically extended the lifespan of mice with Niemann-Pick Type C disease—an inherited genetic disorder that causes neurodegeneration—by 60%, from approximately 75 days to 117 days.

"Our vision is that by boosting BMP, we can improve lysosomal function and slow down brain aging across multiple neurodegenerative diseases involving lysosome dysfunction," Xiong said, highlighting how a deeper understanding of neurodegeneration could help identify potential therapies.

In contrast, Assistant Professor of Medicine Pascal Geldsetzer highlighted how public health measures can also target neurodegenerative disease. By leveraging a “natural experiment” created by a Welsh vaccine program’s strict age requirements, Geldsetzer showed that receiving the shingles vaccine reduces dementia risk by approximately 20% over the following seven years, a finding his team has now replicated across a range of populations.

"Every time we analyze a new high-quality dataset, we keep seeing this strong protective signal," Geldsetzer said. While the precise mechanism remains under investigation, it could have a major impact. Given the ease and relatively low cost of vaccination, “this would be a really important finding for dementia research but also for population health,” Geldsetzer said.

The community of discovery

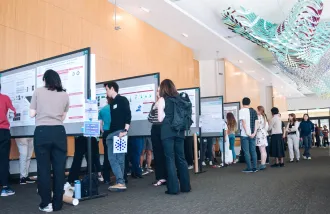

The symposium closed with a poster session that demonstrated how insights from seemingly disparate fields—immunology, metabolism, bioengineering, computer science—converge to address the complex challenge of brain resilience.

The 72 projects presented ranged from investigating bacterial influences on brain tumors (Ella Moore) and exploring RNA mechanisms that protect against cellular stress (Anushka Sanyal) to a study of exercise-induced neuroprotection against delirium (Bun Aoyama) and applying machine learning to detect subtle movement abnormalities in early Parkinson's disease (Madison Yang).

"It's really wonderful to see the energy and people participating and sharing their data, especially students presenting their first poster," Wyss-Coray said. “It's been two-and-a-half years that the Knight Initiative has been operating, and this is the fruit of all this hard work and investment that people put into new research.”