From ambitious efforts to map healthy brain aging to surprising new discoveries about the biology of neurodegenerative disease, the frontier science at the heart of the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at Stanford’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute were on full display at the initiative’s 2025 Fall Symposium.

The event convened researchers from Stanford University, the Allen Institute for Brain Science, the University of California, San Francisco, and University College London to discuss the latest insights into the growing science of brain resilience and emerging opportunities to combat neurodegenerative disease.

Knight Initiative Director Tony Wyss-Coray, the D.H. Chen Distinguished Professor of Neurology and Neurological Sciences at Stanford Medicine, was impressed by what he saw.

Even Wyss-Coray—a leader in brain aging research—was impressed by the day’s cutting-edge presentations. “My mind was blown,” he said.

The heart of the matter

As is now tradition, the symposium began with a conversation with a patient living with neurodegenerative disease—a reminder, Wyss-Coray said, that the Knight Initiative’s ultimate purpose is to improve the lives of real people.

This time, that discussion came with a twist: The patient, Christopher Campos, is himself a neurologist at UC Davis living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.

Speaking with Stanford Medicine neurologist John Day, Campos described how he grew concerned about a muscle twitch that developed early in his medical training.

At first his neurologist friends weren’t too concerned—until things got progressively worse.

“Looking back, I also had severe fatigue. I was tired all the time from all those years as a resident, but this was a new level,” Campos said. Two years after he first experienced the muscle twitches, he was finally diagnosed with ALS.

Now, Campos said, he also experiences less well-known emotional symptoms of ALS, although often not in a textbook way. For instance, he was taught that ALS patients sometimes laugh or cry inappropriately. Campos instead notices differences in how easily he cries or the way he laughs. “It’s not my laugh,” he said. “A lot of the symptoms you experience are different from how they’re taught to you.”

His experience has changed how he thinks about diagnosing and treating neurological disease. “When I try to read case reports, my head spins because there’s so much variability,” Campos said. “It’s really important to listen to all those stories. There’s not one way the disease progresses.”

The brain in full

Allen Institute for Brain Science Director Hongzui Zeng kicked off the afternoon’s scientific talks describing her team’s efforts to understand how cell types in mouse brains change during healthy aging.

Zeng said she was awed by the discovery of “mind-boggling complexity” in the range and organization of cell types in the mouse brain, Zeng said. Drawing on single-cell RNA sequencing and computational techniques, Allen Institute researchers developed an atlas of over 5,000 clusters of cell types that fell into 34 different classes across the whole brain. Earlier this year, Zeng’s team used similar methods to map out how mouse brains change as they age. Among other things, mice create fewer new neurons and experience stronger immune responses and inflammation as they age.

Later in the day, Knight Initiative Brain Resilience Lab Director Alina Isakova described her lab’s flagship effort, the Human Aging Census, which includes data on 34 brains from people aged 20 to 100 who died without signs of neurological disease. The team aims to construct a detailed molecular map of the aging brain, including data on gene expression, proteins, and lipids, to identify how these change over time. Already, lab researchers have found that patterns of gene expression vary across regions as people age, especially in the brain’s vasculature and white matter.

In addition to those research aims, Isakova’s team is also working on new tools, including a ChatGPT-like interface that searches the lab’s data and connects it to “global knowledge” to answer users’ specialized questions about genes, disease, and potential therapies.

Ultimately, the aim is to deepen our biological understanding of aging, Isakova said. “In the next five years, we want to develop a molecular definition of brain aging. Instead of saying, ‘we get a little forgetful,’ we want to say exactly which cell types and which brain areas are involved, by how much, and which molecules actually change,” she said.

New takes on old problems

A second set of researchers spoke specifically to questions about inflammation, neuron health, and neurodegenerative disease.

Andrew Yang, a former Stanford Bioengineering graduate student in Wyss-Coray’s lab, now an assistant professor at UC San Francisco and the Gladstone Institutes, began with an observation: If we understood better how immune cells make their way in and out of the brain, we might be able to harness them to help treat neurodegenerative disease. Yang’s lab is particularly interested in immune cells known as T cells, which researchers once thought could not get into the brain at all. In fact, they can travel into the brain, and Yang’s lab is working on how they could encourage them to stay there to deliver beneficial substances or remove damaged cells.

Xuchen Zhang, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Thomas Südhof, the Avram Goldstein Professor in the Stanford School of Medicine, took on a similarly bold idea: Whether it might be possible to reconstruct the connections between neurons, called synapses, in aging brains affected by neurodegeneration. In recently published work, Zhang, Südhof, and colleagues revealed the molecular mechanisms needed in order for synapses to form. Those details, Zhang said, have inspired an effort to find potential drugs that could encourage synapse formation and perhaps slow neurodegenerative disease.

The day then shifted from restoring synapses to how they might be damaged in the first place. University College London neuroscientist Soyon Hong focused on immune cells called microglia, which studies have shown play important roles in synapse loss and neurodegeneration. Hong and her lab have found that these immune cells interact with astrocytes, a kind of cell that supports neurons, to remove synapses. Ordinarily, astrocytes have a leafy, tree-like structure, but they can turn bulbous in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease—a malfunction that may contribute to abnormal microglia activation and synapse damage. What’s more, astrocyte malfunction depends on a gene called APOE, one of the highest genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s. Now, the team is using CRISPR gene editing in mice to test whether those effects are rescued in mice and perhaps prevent Alzheimer’s from developing.

The next generation

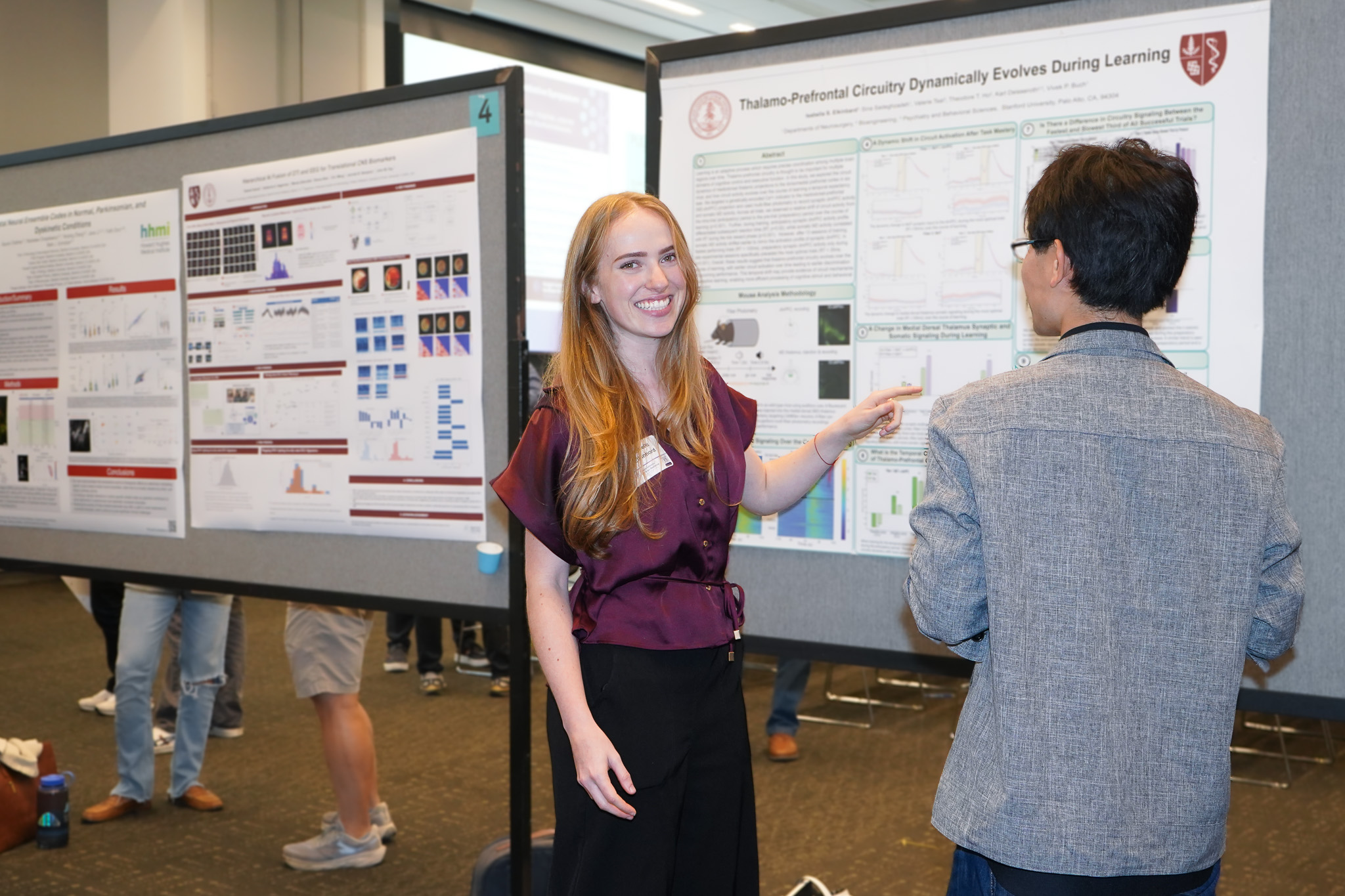

The afternoon wrapped up with a poster session featuring 38 graduate students and postdoctoral fellows presenting research on a range of topics linked to aging and brain health. Topics included the vulnerability of neurons responsible for movement in ALS, brain inflammation in response to surgery in older adults, and the nature of gut microbiome changes related to Parkinson’s disease.

“I think these talks and posters were fantastic. I’m so inspired, and I hope you were too,” Wyss-Coray said.