If there’s one thing that’s crystal clear about Alzheimer’s disease, it’s this: It eats away at neurons and the links between them, ultimately destroying the neural networks that underlie our memories.

Exactly how the disease does that remains unclear. According to one popular theory, a protein fragment called amyloid beta builds up in the brain and damages neurons. But there are a host of other possibilities related to tau proteins, lysosomes, neuroinflammation, immune cells called microglia, and more.

Now, researchers think they’ve found a way to merge two of those theories into one. In a paper published September 18 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team adds to the evidence that amyloid beta and inflammation converge on a single point: a chemical receptor that tells neurons in the brain when to remove the links between neurons, called synapses.

Two lines of research combine in the new study, which was led by Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute affiliate Carla Shatz, the Sapp Family Provostial Professor and Barbara Brott, the paper's first author and a research scientist in Shatz's lab. The study was funded in part by a Catalyst Award from the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, which among other things aims to rethink the basic biology of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

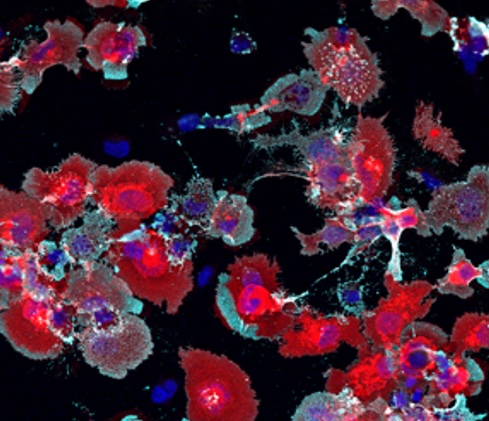

The first line of research involves a receptor molecule called LilrB2, one that Shatz is intimately familiar with. In 2006, she and colleagues found that the mouse equivalent of LilrB2 plays a key role in “pruning” synapses, a normal part of brain development and adult learning. But there are links to Alzheimer’s as well: In 2013, the team showed that amyloid beta binds to the same receptor, and when it does, it triggers neurons to prune synapses. What’s more, genetically eliminating the receptor prevents memory loss in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s.

The second line of research concerns an inflammatory process called the complement cascade. Ordinarily, the process produces a shower of molecules that help clear viruses, bacteria, and infected cells from the body. But inflammation is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s, and recent studies have linked the complement cascade in particular to synaptic pruning and neurological disease.

That got Shatz wondering whether the complement cascade, like amyloid beta, might also activate the LilrB2 receptor, triggering synaptic pruning.

To find out, the team first ran screens to see if any complement cascade molecules would bind to that receptor. They found one, and only one: C4d, which bound tightly enough to the receptor that the team thought it might contribute to synapse loss.

To put that hypothesis to the test, they pumped C4d directly into the brains of ordinary mice. “Lo and behold, it stripped synapses off neurons,” Shatz said—quite a surprise for a molecule researchers had previously thought had no function at all.

The upshot of all of this is that amyloid beta and neuroinflammation may contribute to synapse loss through a common mechanism—and that may call for a reevaluation of how Alzheimer’s disease destroys memory.

“There’s an entire set of molecules and pathways that lead from inflammation to synapse loss that may not have received the attention they deserve,” said Shatz, who is also a professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences and of neurobiology in the School of Medicine.

The results also challenge a view held by many in the field that glia—the brain’s immune cells—are principally responsible for synapse loss in Alzheimer’s. “Neurons aren’t innocent bystanders,” Shatz said. “They are active participants.”

And, Shatz said, that observation may have a direct impact on treatment. Right now, the only FDA-approved drugs to treat Alzheimer’s attempt to break up amyloid plaques in the brain. But “busting up amyloid plaques hasn't worked that well, and there are a lot of side effects,” such as headaches and brain bleeding, Shatz said. “And even if they worked well, you’re only going to solve part of the problem.”

The better solution may be by targeting receptors such as LilrB2 that are directly responsible for synapse loss—and by protecting synapses, Shatz said, we can protect memory as well.

Publication Details

Research Team

The study authors are Barbara Brott, Aram Raissi, Monique Mendes, Caroline Baccus, Jolie Huang and Carla Shatz from the Stanford University Department of Biology, Stanford Medicine's Department of Neurobiology, and Bio-X; Kristina Micheva from Stanford's Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology; and Jost Vielmetter from the California Institute of Technology.

Research Support

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01AG065206 and 1R01EY02858), the Sapp Family Foundation, the Champalimaud Foundation, the Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, the Ruth K. Broad Biomedical Research Foundation, and the Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at the Wu Tsai Neuroscience Institute Stanford University. Human Alzheimer’s disease tissue samples were also provided by the Neurodegenerative Disease Brain Bank at the University of California, San Francisco, which receives funding support from the NIH (P01AG019724 and P50AG023501), the Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research, and the Tau Consortium.

Competing Interests

Micheva has founder’s equity interests in Aratome, LLC (Menlo Park, CA), an enterprise that produces array tomography materials and service. She is also listed as inventor on two United States patents regarding array tomography methods that have been issued to Stanford University (United States patents 7,767,414 and 9,008,378). All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.