The two neurodegenerative diseases could not appear more different. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), sometimes called Lou Gehrig’s disease, affects the muscles, ultimately paralyzing people with the disorder. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which has been in the news of late, is a form of dementia that can change someone’s personality and rob them of their ability to understand language.

But ALS and FTD turn out to have a great deal in common at the molecular level, and researchers at the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at Stanford’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute believe that a treatment for either disorder will ultimately help patients with both conditions.

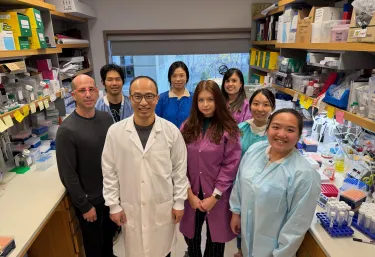

Brain Resilience Postdoctoral Research Fellow Yi Zeng, his mentor Stanford Medicine Basic Science Professor and Professor of Genetics Aaron Gitler, and Gitler’s lab have been working for a while to better understand these connections, and they recently published a study on what happens when a key protein linked to ALS and FTD goes wrong.

We caught up with Zeng to talk about what ALS and FTD share, his latest research, and what diagnostics and therapies might emerge in the future.

FTD and ALS have different symptoms and present themselves very differently. How are these diseases linked and how did researchers discover this link?

Yes, these diseases look quite different clinically. ALS primarily affects movement, causing progressive muscle weakness and paralysis, while FTD affects behavior, personality, and language.

The breakthrough came in 2006 when researchers examined postmortem brain and spinal cord tissue from patients. They discovered that the same protein, TDP-43, formed abnormal clumps in both diseases. This was remarkable because it revealed these seemingly distinct diseases share the same underlying molecular problem.

What made this even more compelling was how common this is: TDP-43 clumps are found in about 97% of ALS cases and up to 50% of FTD cases. We now understand these diseases exist on a spectrum—some patients show features of both, and some families have members who develop ALS while others develop FTD from the same genetic mutation.

Which disease emerges depends on which brain regions are most affected—motor neurons in the spinal cord in ALS versus frontal and temporal lobes of the brain in FTD. This shared molecular basis has fundamentally changed the field, because therapies targeting TDP-43 dysfunction could potentially benefit both conditions.

What does TDP-43 do when it's working properly?

Your DNA is like a master cookbook locked in the nucleus. To make proteins, cells first copy recipes from DNA into RNA—but these are rough drafts that need editing before they can be used.

Think of TDP-43 as a chief editor in that process. It performs two critical jobs:

First, it decides which parts to keep and which to remove, through a process called splicing. Genes contain useful sections called exons and unnecessary sections called introns. TDP-43 helps cut out introns and connect exons in the right order, like removing unwanted paragraphs and connecting the good ones.

Second—and this is what our study focused on—TDP-43 decides where the RNA message should end, through a process called polyadenylation. Think of it like deciding where to put the period at the end of a sentence. Put the period in the wrong place, and you completely change the meaning.

When TDP-43 stops working properly in ALS and FTD, these editing decisions go wrong. The wrong pieces get included, messages end in the wrong places, and neurons start to malfunction and ultimately die.

What did we know about how that process goes wrong?

Before our work, researchers had made several important discoveries. First, in ALS and FTD patients, TDP-43 leaves the cell nucleus where it normally works and forms toxic clumps in the cytoplasm. This creates two problems: the editor abandons its post, so mRNA doesn't get edited properly, and those clumps themselves are toxic to the cell.

Second, when TDP-43 is dysfunctional, cells include “cryptic” exons in their RNA messages—pieces of RNA that should have been cut out. It's like the editor is gone, so unwanted paragraphs end up in the final version. When cryptic exons get included, these faulty RNA messages lead to less functional protein.

When we started our work, the field was intensely focused on splicing as the major consequence of TDP-43 loss. There was a growing list of genes with cryptic exons, and people were developing therapeutics to fix these specific splicing defects. At the same time there were hints that TDP-43 could also affect where the RNA message ends—that “period at the end of the sentence.”

However, no one had systematically studied how widespread or important these polyadenylation changes were. That's the gap we set out to fill.

You’ve recently published a paper on polyadenylation. What did you learn?

I suspected we’d been seeing only part of the problem—the splicing part—and you can’t develop effective therapies if you're missing part of the problem. We then asked whether TDP-43 loss significantly affects polyadenylation. If so, how many genes? Do they contribute to disease? To study this, we used 3' end sequencing, which maps exactly where each RNA ends, like having GPS coordinates instead of a general map.

We discovered that TDP-43 dysfunction causes widespread polyadenylation defects in hundreds of genes, revealing a new dimension of RNA misprocessing in ALS and FTD. These changes affect genes critical for neurons and genes already linked to disease. Critically, we validated these in patient samples, confirming they happen in actual patients. Mechanistically, we found that both how strongly TDP-43 binds and where it binds to RNA matter.

What excites me most is the convergence. Three independent labs—ours and two others—published simultaneously using different approaches but reaching the same fundamental conclusion. Together, we're beginning to see a more complete picture of TDP-43 dysfunction. For years, we've known it causes splicing defects—the editor failing to remove unwanted paragraphs. Now we know it causes polyadenylation defects—failing to place the period correctly. Both affect hundreds of genes critical for neuron survival. These discoveries are major steps forward in understanding how losing this master editor causes neurodegeneration.

How do you think these results will help move the field forward? Could we potentially now design drugs to treat these diseases?

These findings advance the field in important ways, though we need to be realistic about timelines.

Most immediately, these discoveries could help develop better biomarkers. The field desperately needs ways to detect and track TDP-43 pathology in living patients. These polyadenylation changes could potentially help diagnose TDP-43 pathology if we can detect them in accessible samples like spinal fluid, track disease progression over time, or measure whether experimental therapies are actually restoring TDP-43 function. This biomarker potential is particularly exciting because it's more immediately achievable than therapeutic applications.

For therapeutic development, these findings expand our understanding of what needs to be addressed. We've now identified hundreds of genes with polyadenylation defects in addition to the known splicing problems. This more complete picture of TDP-43 dysfunction helps us understand the full scope of the problem, which is essential groundwork for developing effective treatments, though translating this knowledge into therapies will take considerable time and effort.

What's most exciting to me is that for two decades, we've known TDP-43 goes wrong in ALS and FTD. We've recently understood it causes splicing defects. Now we know polyadenylation defects are equally widespread. We're beginning to see a more complete picture of how TDP-43 dysfunction damages neurons. And having that complete picture is essential for developing solutions.

Publication Details

Research Team

Study authors were Yi Zeng of the Department of Genetics at the Stanford School of Medicine and the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience; Anastasiia Lovchykova, Tetsuya Akiyama, Chang Liu, Odilia Sianto, and Caiwei Guo of the Department of Genetics at Stanford Medicine; Stephanie L. Rayner of the Department of Genetics at Stanford Medicine and Macquarie University; Vidhya Maheswari Jawahar, Anna Calliari, Mercedes Prudencio, Dennis W. Dickson and Leonard Petrucelli of the Mayo Clinic; and Aaron D. Gitler of the Department of Genetics at Stanford Medicine, the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub.

Research Support

The study was supported by the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, the National Institutes of Health Training Program in Aging Research (2T32AG047126-06A1), the Takeda Science Foundation, FightMND, a Stanford School of Medicine Dean’s postdoctoral fellowship, the Milton Safenowitz Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, the National Institutes of Health (U54NS123743, R35NS097273, P01NS084974, U54NS123743, RF1NS120992, R35NS137159, U54NS123743 and R01AG064690), and Target ALS.

Competing Interests

Gitler is a scientific founder of Maze Therapeutics, Trace Neuroscience and Lyterian Therapeutics. The other authors declare no competing interests.