Early disease detection and treatment, new drug candidates, and brain cells’ garbage disposal systems were among the topics researchers discussed at the Winter 2026 Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience Symposium.

Held January 27th, the event was the tenth such symposium in four years and attracted 350 registrants, said Knight Initiative Director Tony Wyss-Coray, the D.H. Chen Distinguished Professor of Neurology and Neurological Sciences.

“It’s really exciting to have another terrific group of speakers here and have you all come out and be part of this community,” Wyss-Coray said.

Early warning signs

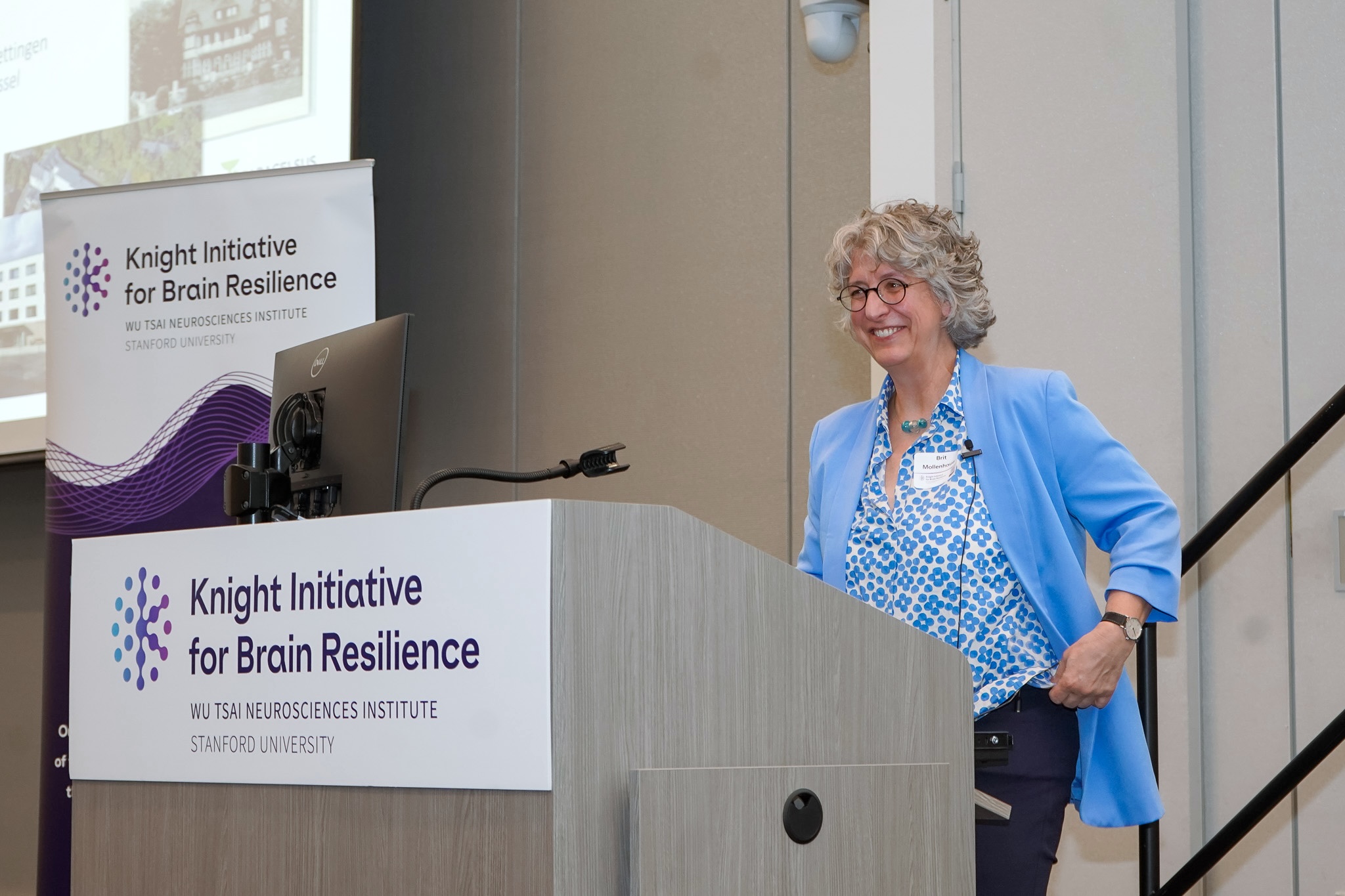

One sad fact stands out about clinical trials aimed at slowing or preventing Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative motor diseases, said Brit Mollenhauer, a professor of neurology at the University of Göttingen: They’ve pretty much all failed.

The reasons aren’t complicated, Mollenhauer said. First, there are few reliable biomarkers of Parkinson’s. The exception is alpha synuclein, a protein that collects in cerebrospinal fluid in Parkinson’s patients. Tests that search for alpha synuclein in CSF have been transformative, Mollenhauer said. But they’d be even more valuable if they could be done in peripheral samples such as blood, which is easier to access, or go beyond current tests and indicate how far Parkinson’s has progressed.

Second, most people today are diagnosed with Parkinson’s after movement symptoms begin—in part because biomarker tests that could detect the disease early have only been developed in the last few years. That’s made it difficult to study patients from the earliest stages of disease.

Mollenhauer is hoping to change that. She and her lab are following large cohorts of people to find out if alpha synuclein in blood or skin samples—or even nasal swabs—might identify those most likely to develop motor disorders. And they’re investigating whether simple dietary interventions, such as occasional fasting or diets with resistant starch, might slow or prevent disease progression.

Living with Parkinson’s disease

Since the beginning of the Knight Initiative, each symposium has featured a patient living with neurodegenerative disease—a reminder, Wyss-Coray said, of the human impact of the diseases Knight Initiative researchers and others are working to understand.

This time around, Gaurav Chattree, a neurologist at Stanford Medicine, spoke with his patient Walter Chang, who has been living with Parkinson’s disease for the last two decades.

Chang—who has always been an active person—first noticed symptoms when he was running on a treadmill and discovered his left foot dragging a bit. Eventually he developed other motor symptoms, including gait freezing, and began treatment with L-DOPA, currently the only drug treatment for the disease.

L-DOPA, however, has some unpleasant side effects, especially after taking it for a long time, including problems with impulse control. “That was the most devastating side effect,” Chang said.

Although it didn’t address all his symptoms—notably gait freezing—Chang has now turned to deep brain stimulation, which allows him to take less medication and experience fewer side effects. And, he said, he remains active with boxing, tai chi, spin classes and other sports, something Chattree encouraged. “We really emphasize exercise as treatment,” Chattree said.

Lipid blobs and neurodegeneration

A lot of us seem to store more fat as we age, but it’s not just in our tummies—it turns out to be true all the way down to the cellular level. In healthy aging and especially in neurodegenerative disease, our cells form more blobs called lipid droplets that among other things protect toxic lipid buildups.

Yet exactly how those droplets are connected to aging isn’t clear, said James Olzmann, a cell biologist at the University of California, Berkeley. Olzmann’s lab studies what he called “lipid quality control systems,” with an eye toward understanding the link to ferroptosis, a kind of cell death caused by lipid buildup that’s also been linked to Parkinson’s disease.

Using genetic screens and other methods, Olzmann’s lab recently discovered a protein that prevents damage to lipids in cell membranes and inside lipid droplets, which in turn prevents ferroptosis. Now, they’re investigating a possible drug to target that protein, appropriately dubbed Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1, or FSP1. By inhibiting its function, early studies show, researchers may be able to target and kill cancer cells. Perhaps, Olzmann said, stimulating FSP1 could also potentially prevent cell death that leads to neurodegeneration.

A journey from from cells to treatments

A lot has been said about what causes Alzheimer’s disease, but what ultimately matters is synapses—the electrical relays that link neurons together—said Frank Longo, the George E. and Lucy Becker Professor of Medicine and a professor of neurology at Stanford Medicine.

“Loss of synapses is the bottom line of many of these neurodegenerative diseases,” Longo, a Wu Tsai Neuro affiliate, told the audience. Longo described his decades-long journey studying the underlying mechanisms of synapse loss to developing a drug treatment that’s now in clinical trials.

The path started in the early 2000s with a protein called p75 that helps regulate synapses and nervous system development. Knocking out p75 in mice, Longo and his lab found, made synapses more resilient to aging. The lab then developed a small molecule compound to target p75 and tested it in individual cells, then mice, then larger animals—and eventually in humans. The drug has proved to be safe and shown early signs of slowing cognitive decline.

It’s a long way from where he started, Longo said. At a recent visit to a clinic in Barcelona where the drug was being tested, he caught sight of a blister pack of the drug he’d helped develop. The blister pack was empty, meaning that someone had actually taken the medicine he’d been working toward for years. “It brought me to tears,” Longo said.

Aging organs might predict brain health

Aging is not a uniform process, explained Daisy Ding, a postdoctoral fellow in the Wyss-Coray lab: Recent research from the Wyss-Coray lab shows that different organs age at different rates and that the biological age of an organ doesn’t necessarily correspond to a person’s chronological age.

The group had previously shown that the biological age of organs can predict how long a person will live and what diseases they are at risk of developing. Now, Ding and colleagues are working to understand whether proteins in the blood can also be used to track the age of specific cell types in tissues as diverse as muscle, lung, or the brain and whether their age can foretell disease and mortality.

In a paper posted as a preprint (not yet peer reviewed) at bioRxiv.org, they report aging of specific types of cells can predict how long a person will live, whether they will develop diseases such as lung cancer—independent of such factors as smoking—and whether a person is likely to experience neurodegenerative disease.

Proteins up to no good

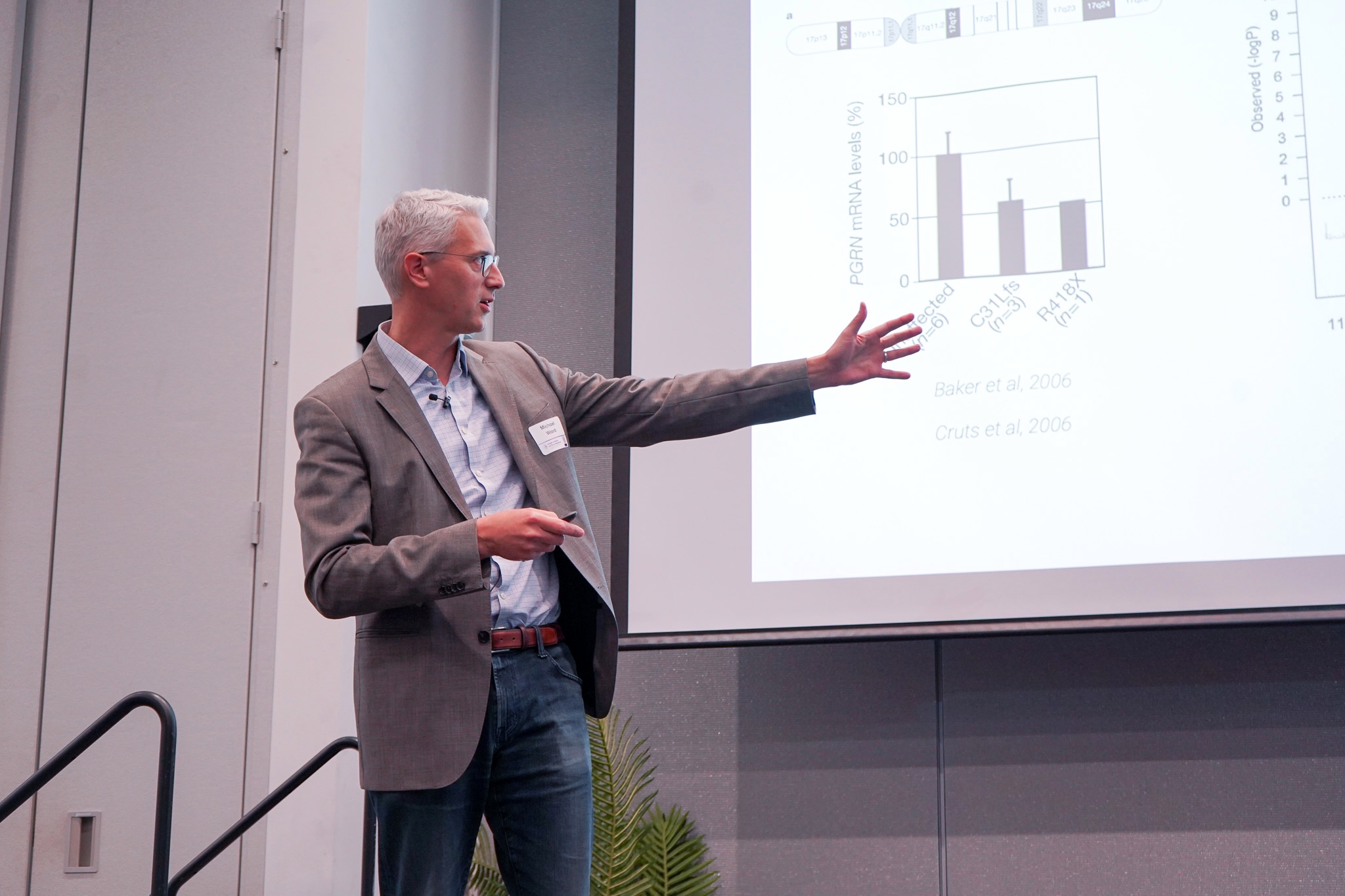

Michael Ward, a senior investigator at the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke, closed out the day’s talks with a tale of two genes that “conspire together to drive neurodegeneration,” Ward said.

His research centers on the molecular underpinnings of diseases including frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. Over the last several years, they’ve homed in on two proteins, TMEM106B and progranulin. Those proteins are interesting in part because they meet up inside cells’ waste management machines, called lysosomes, which have been linked to neurodegeneration.

Now, Ward’s lab is working to better understand how genetic variants of the two proteins could work together to damage lysosomes, disrupting or even killing off neurons. At the same time, the team is working on ways to head off that damage, which could point toward potential treatments or preventative measures for neurodegenerative disease down the road.

The conversation continues

The day closed with poster presentations from 29 Stanford researchers representing 12 departments across Stanford Medicine, Engineering, and Humanities and Sciences, along with the Stanford Cancer Institute and two Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute community labs.

Those posters covered an equally diverse range of topics, including the genetics of aging, nanoparticle tools and other methods for studying neurodegenerative disease, and even a podcast on magnetic resonance imaging in medicine and biology.

A feeling of hope emerged as attendees and researchers discussed those projects, Wyss-Coray said.

"It's wonderful to see how this brain resilience community has come together over the first three years of the Knight Initiative, and the incredible research that's come out of that," he said. "I can't wait to see what comes next."