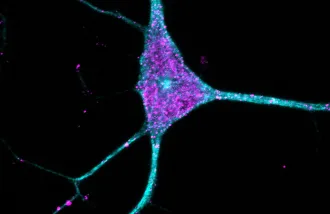

Functioning brain cells need a functioning system for picking up the trash and sorting the recycling. But when the cellular sanitation machines responsible for those tasks, called lysosomes, break down or get overwhelmed, it can increase the risk of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other neurological disorders.

“Lysosomal function is essential for brain health, and mutations in lysosomal genes are risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases,” said Monther Abu-Remaileh, a Wu Tsai Neuro affiliate and an assistant professor of chemical engineering in the Stanford School of Engineering and an assistant professor of genetics in the Stanford School of Medicine.

The trouble is, scientists aren’t sure exactly how lysosomes do their work, what’s going wrong with lysosomes that leads to neurodegeneration—or even in which cell types neurodegenerative disease begins. There might even be other lysosomal disorders yet to be discovered.

That may be about to change. In a new study, researchers backed by a Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience Catalyst Momentum Award have laid out the first-ever atlas of lysosomal proteins in the brain, indicating which proteins are most closely associated with lysosomes across different brain cell types. That data, the researchers say, could help scientists better understand what lysosomes are up to and what happens when they break down.

“Now we know which lysosomal proteins are enriched in which brain cell types,” said Ali Ghoochani, a research scientist in Abu-Remaileh’s lab and co-first author on the new paper. “This allows us to better understand the functions of these proteins and how their dysfunction contributes to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurological disorders.”

In fact, the data has already yielded new results. As the team reported January 22 in Cell, they used the atlas to tie a rare neurological disorder, SLC45A1-associated disease, to lysosomal dysfunction. And, with a dedicated website where others can access the data, that’s just the beginning, Abu-Remaileh said.

Steady progress

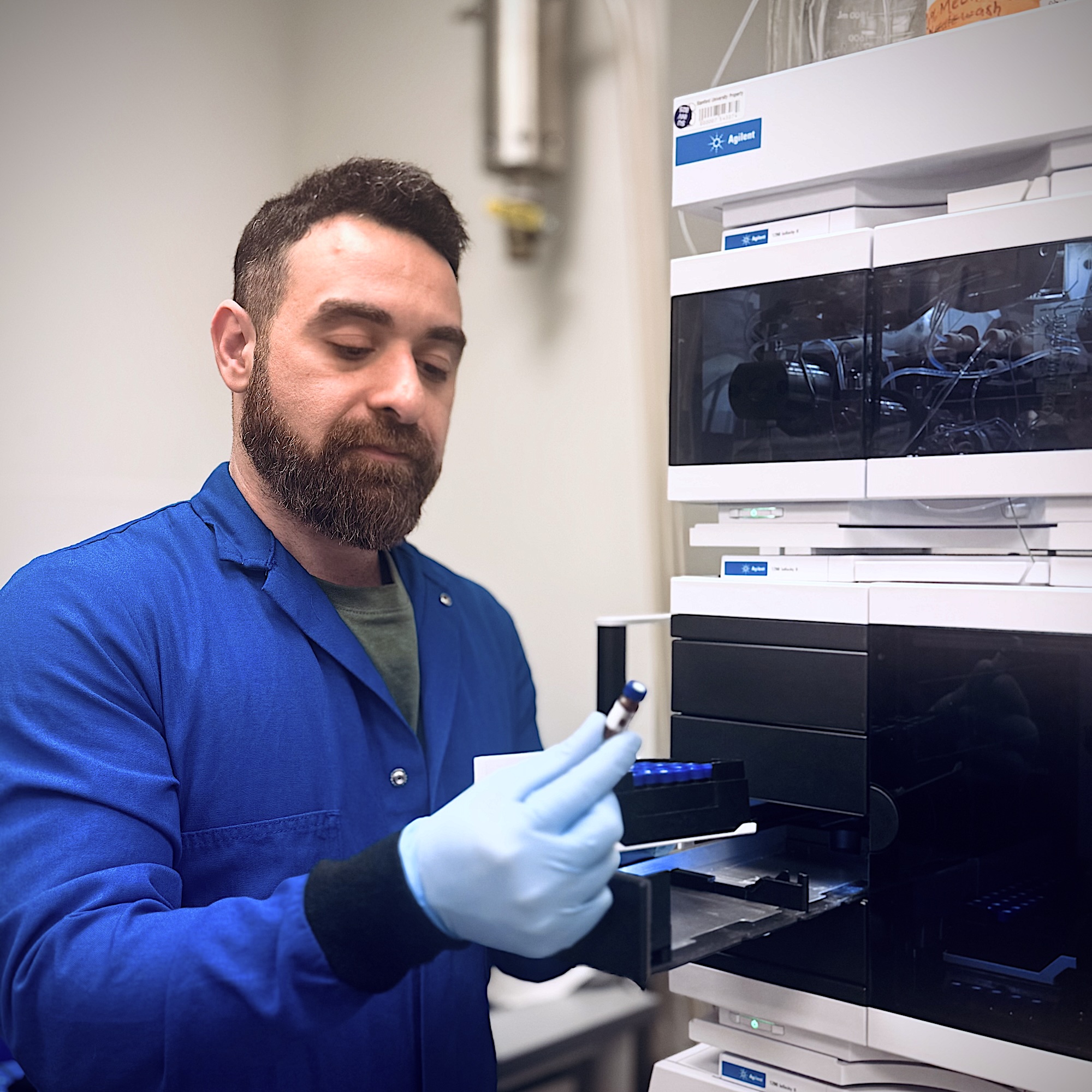

The new study builds on esearch that started when Abu-Remaileh’s group began applying proteomics—the systematic examination of the proteins present in an organism—specifically to lysosomes. The hard part, they realized, was isolating lysosomes from other cellular machinery in a way that preserved the chemistry within.

In a 2017 paper, Abu-Remaileh reported a new method called LysoIP that tags lysosomes so they could be removed from other cellular components and studied independently. In 2022, his lab extended that technique to genetically modify mice so that their lysosomes would express the tag automatically. Drawing on that method, called LysoTag, Abu-Remaileh’s lab discovered the role that a particular protein, CLN3, played in breaking down lipids—and how the loss of CLN3 could lead to Batten disease, a rare childhood disorder in which cells accumulate waste, leading to seizures, problems thinking and moving, and ultimately death.

LysoTag’s success got Ghoochani, Abu-Remaileh, and their colleagues thinking: If they knew more about where proteins like CLN3 shows up the most in the brain they might learn more about their functions and dysfunctions.

“What we wanted to do here was to use that technology to be able to see what the composition of the lysosome is in different cell types in the brain,” Abu-Remaileh said. “We thought by doing so, we might be able to tell which lysosomes in which cell types are the culprits in different genetic neurodegenerative diseases.”

Figuring that out could help researchers and doctors better understand neurodegeneration and perhaps point toward new therapeutics.

With support from the Knight Initiative and the Metabolomics Group at the Nucleus at Stanford’s Sarafan ChEM-H, Ghoochani and colleagues first extended LysoTag’s capabilities, combining it with a method for targeting it to specific cells. That way, they could add LysoTag to specific cell types and extract lysosomal proteins specifically from each of the four major brain cell types—neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. Working with Julia Heiby and Allesandro Ori at the Leibniz Institute on Aging, the researchers then developed data analysis tools to identify which proteins were most closely associated with lysosomes from each of the four brain cell types.

Expanding the map

With those tools in hand, the team built their atlas: a catalog of 790 proteins associated with lysosomes—that is, more likely to be found in lysosomes than elsewhere—along with data on which proteins were more likely to be found in which types of brain cells.

That atlas presented the researchers with an unusual opportunity to explore connections between lysosomal proteins, the genes that encode them, and neurodegenerative disease. In particular, the team found 67 lysosomal proteins associated with Alzheimer’s-related dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and lysosomal storage disorders. A few of those proteins, further analysis showed, were expressed more in one cell type than others—for example, a protein called GRN associated with frontotemporal dementia was more common in microglia, a kind of immune cell that has been linked to neurodegeneration, than others. That, Ghoochani and Abu-Remaileh said, meant they had an unusual opportunity to study links between disease and lysosomal dysfunction.

Another protein in the list raised the team’s eyebrows. The researchers knew that protein SLC45A1 helps transport sugars across cell membranes and that mutations in the protein cause intellectual disabilities with neuropsychiatric symptoms—but no one had previously connected it to the lysosome or lysosome dysfunction.

To investigate further, Ghoochani performed a series of tests in cultured cells, looking for signs of lysosomal dysfunction. Indeed, he found that the loss of SLC45A1 disrupts lysosomal degradation—the process of breaking apart waste—which makes it harder for lysosomes to clear that waste out. That strongly indicated SLC45A1-associated disease as a lysosomal storage disorder.

That finding, the researchers believe, is just the beginning. One project, Ghoochani said, aims to better understand the function of SLC45A1 in lysosomes, which could eventually inform approaches to therapeutics.

There are possibilities as well. “Now that we have the atlas, there are many proteins with potential disease relevance that we plan to investigate further.” Ghoochani said.

Other labs are getting excited by that prospect, too, Abu-Remaileh said, thanks to the website where researchers can scour the atlas for ideas. “People are already using our approach to look at disease in different cell types, and there are plenty of labs following in Ali’s footsteps in doing cell-type specific work on the lysosome in disease models.”

Publication Details

Research Team

Study authors were Ali Ghoochani, Eshaan S. Rawat, Uche N. Medoh, Wentao Dong, Kwamina Nyame, and Nouf N. Laqtom from the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Stanford School of Engineering, the Department of Genetics at the Stanford School of Medicine, Sarafan ChEM-H, and the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Collaborative Research Network; Julia C. Heiby from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Stanford Engineering, the Department of Genetics at Stanford Medicine, Sarafan ChEM-H, and the Leibniz Institute on Aging at the Fritz Lipmann Institute; Domenico Di Fraia from the Leibniz Institute on Aging, the Cluster of Excellence on Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases, and the University of Rochester; Marc Gastou and Natalia Gomez-Ospina from the Department of Pediatrics at Stanford Medicine; Mohit Rastogi from the Institute for Stem Cell Biology & Regenerative Medicine and the Department of Pathology at Stanford Medicine; Vincent Hernandez from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Stanford Engineering, the Department of Genetics at Stanford Medicine and Stanford ChEM-H; William Durso, Christina Valkova, Christoph Kaether, and Alessandro Ori from the Leibniz Institute on Aging at the Fritz Lipmann Institute; Alina Isakova from The Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Stanford University; Marius Wernig from the Institute for Stem Cell Biology & Regenerative Medicine, the Department of Pathology, and Department of Chemical and Systems Biology at Stanford Medicine; Christian Franke from Friedrich Schiller University Jena; and Monther Abu-Remaileh from the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Stanford School of Engineering, the Department of Genetics at the Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford ChEM-H, the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Collaborative Research Network, and The Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience.

Research Support

This research was funded in part by Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP-000463) through the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF), Beatbatten, the NCL Foundation, NCL Stiftung, the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award Program (1DP2CA271386), the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at Stanford University, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Neurodegeneration Challenge Network (2024-338545, 2020-221617, 2021-230967, and 2022-250618), the International Neuroimmune Consortium with a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association (ADSF-24-1345203-C), the NIMH (R01MH092931), the German Research Council via the Research Training Group ProMoAge (GRK 2155), Collaborative Research Center PolyTarget (SFB 1278, 316213987, project B07), the Fritz-Thyssen Foundation (award number 10.20.1.022MN), the German Academic Exchange Service Postdoctoral Program, the Thüringer Aufbaubank (TAB, FGR 0060 KI-supER), the American Academy of Neurology, the Sarafan ChEM-H Chemistry/Biology Interface Program Kolluri Fellowship, and Sarafan ChEM-H.

Competing Interests

Abu-Remaileh is a scientific advisory board member of Lycia Therapeutics and advisor for Scenic Biotech. Wernig is a co-founder of Neucyte Inc., a scientific advisor for bit.bio Ltd., and co-founder and scientific advisor of Lyterian Therapeutics and Theseus Therapies.